Pledges made in Glasgow at the recent United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP26, are urgently needed by communities on the front lines of forest loss, according to a new study by a multidisciplinary team from the University of Washington, Duke University and The Nature Conservancy. New research shows how much local temperature rises in the tropics — compounded by accelerating deforestation — may already be jeopardizing the well-being and productivity of outdoor workers.

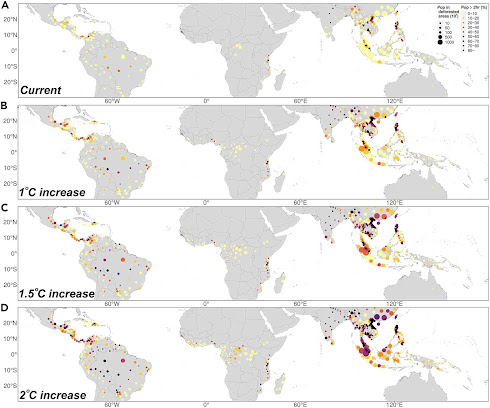

The study, published Dec. 17 in One Earth, compares established recommendations on safe working conditions with satellite observations of temperature and forest cover and population data. Results show how warming associated with recent deforestation, from 2003 to 2018, has increased heat exposure for 4.9 million people globally, including 2.8 million outdoor workers.

“Our findings highlight the vital role tropical forests play in effectively providing natural air-conditioning services for populations vulnerable to climate change — given these are typically regions where outdoor work tends to be the only option for many, and where workers don’t have the luxury of retiring to air-conditioned offices whenever the temperature rises to intolerable levels,” said lead author Luke Parsons, who began the study as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington and is now a postdoctoral researcher at Duke University.

Decreases in safe working hours associated with heat exposure were found to be of particular concern in areas that are deforested, compared with regions where most tropical forest remains intact. The researchers found “hot spots” for deforestation-related heat exposure in Brazil, Belize, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nigeria and Cameroon.

The study also highlights disproportionate heat exposure for populations working in parts of Brazil — warning that future projections of global warming, compounded by unchecked forest loss, will only exacerbate this situation.

In the western state of Mato Grosso and the northern state of Pará, for example — even in the unlikely event of no further deforestation or population growth — the study projects that future global warming of 2 degrees Celsius relative to today could see more than a quarter of a million people lose two more hours of safe working time per day compared with 2003, in just these two recently deforested regions.

“For me, this research highlighted two messages,” Parsons said. “One, that removing tropical rainforest is not only bad for global climate change, but is also bad for local ecosystems and people. And two, if we can prevent tropical deforestation, there is a tangible benefit for the people living in areas with tropical forest.”

Co-authors are Jihoon Jung and Dr. June Spector in environmental and occupational health sciences at the UW; Lucas Vargas Zeppetello and David Battisti in atmospheric sciences at the UW; and Yuta Masuda, Timm Kroeger and Nick Wolff at The Nature Conservancy.

Source/Credit: University of Washington

en121821_01