In the latest issue of the journal Nature, an international team including astronomers from University of Turku reveal the origin of a thermonuclear supernova explosion. Strong emission lines of helium and the first detection of such a supernova in radio waves show that the exploding white dwarf star had a helium-rich companion.

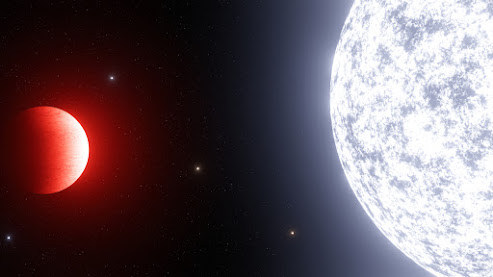

Thermonuclear (Type Ia) supernovae are important for astronomers since they are used to measure the expansion of the Universe. However, the origin of these explosions remains an open question. While it is established that the explosion is that of a compact white dwarf star somehow accreting too much matter from a companion star, the exact process and the nature of the progenitor is not known. The new discovery of supernova SN 2020eyj established that the companion star was a so-called helium star that had lost much of its material just prior to the explosion of the white dwarf.

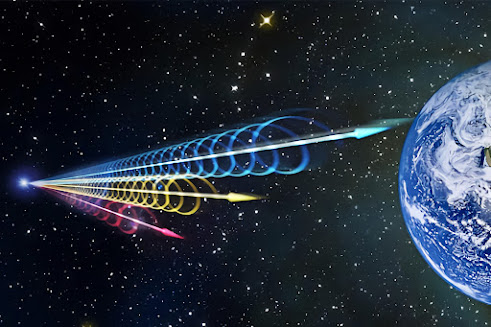

“Once we saw the signatures of strong interaction with the material from the companion, we tried to detect it also in radio emission”, explains Erik Kool, post-doc at the Department of Astronomy at Stockholm University and lead author of the paper. “The detection in radio is actually the first one of a Type Ia supernova – something astronomers have tried to do for decades.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)