|

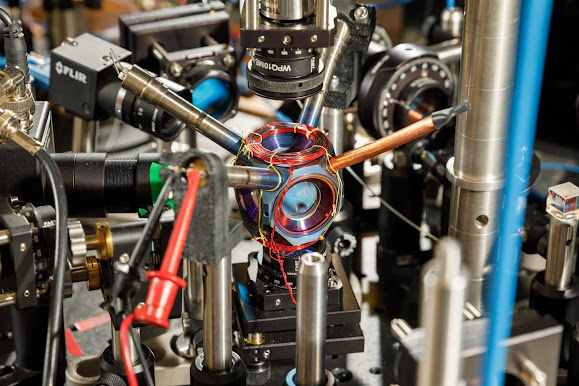

| Stylized scientific image of the anti-inflammatory molecule, Interleukin-37 |

Our body’s own immune system produces many highly potent anti-inflammatory molecules, but they are often highly fragile, short-lived, and do not have drug-like properties. Interleukin-37 is one such molecule produced by the body to turn off inflammation.

Together with partner F. Hoffmann-La Roche (Roche), the multidisciplinary research team from the Monash University Biomedicine Discovery (BDI) Institute, Monash University’s Department of Pediatrics and the Hudson Institute of Medical Research have harnessed their Fc-fusion platform to engineer the next generation of Interleukin-37, one that retains anti-inflammatory potency, is highly stable and has an excellent therapeutic likeness.

The findings from the research collaboration have now been published in Cell Chemical Biology.

A little bit of inflammation can be a good thing and is often the body's immune system doing its job. However, when inflammation persists, or the immune system starts attacking the body’s own cells, this can lead to disease.

One of the study’s lead authors Dr. Andrew Ellisdon from the Monash BDI says many human diseases, including autoimmune diseases such as arthritis or inflammatory bowel disease, are characterized by too much inflammation. There is a gap in producing new generations of potent anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

.jpg)

.jpg)