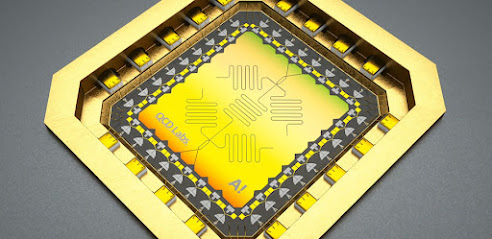

The research team from UWE Bristol’s Big Data lab and Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences (HAS) is developing technology that uses artificial intelligence (AI), augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to assist cardiac surgeons in planning and preparing for complex keyhole heart valve surgery. The team is initially collaborating with the Bristol Heart Institute (BHI), a Specialist Research Institute at the University of Bristol, whose surgeons will test the system when preparing for minimally invasive cardiac valve surgery (MICVS).

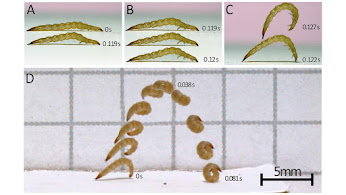

Compared to conventional open-heart surgery involving cutting through the breastbone to reach the heart, MICVS is less intrusive as the heart is accessed through smaller incisions using endoscopic instruments. And patient recovery time is generally quicker after this keyhole surgery.

However, MICVS is complex and requires hours of pre-operative planning and preparation.

Dr Hunaid Vohra, Consultant Cardiac Surgeon and Honorary Senior Lecturer and Researcher at the BHI, who is collaborating with UWE Bristol, said: “In the operating room, despite pre-planning, it is currently very common to find unexpected challenges, as every patient’s height, weight and heart-lung anatomy is different. And patients’ frailty varies.

.jpg)