Professor Jukka Pekola and Doctoral Candidate Bayan Karimi from Aalto University propose a new approach to measure the energy of single microwave photons. These low energy quanta are emitted by artificial quantum systems such as superconducting qubits. Detecting them continuously has been challenging but would be useful in quantum information processing and other quantum technologies.

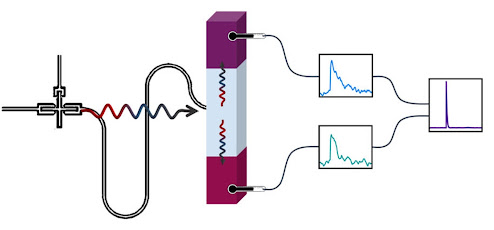

A photon is produced when a superconducting qubit transits between states, radiating energy into its environment. The researchers capture the tiny energy of this photon by transferring it into heat. The new technique relies on splitting the energy of a photon across two independent heat baths and making measurements using two uncoupled detectors at once. This would significantly enhance the signal-to-noise ratio, making it easier to detect an absorption event and its energy.

‘In our proposed setup the energy of a qubit is large whereas its typical operating temperature is very low. This contrast opened an opportunity to solve the Schrödinger equation exactly for up to one million external oscillators forming the heat baths in the model describing this measurement,’ Pekola says.

.jpg)