|

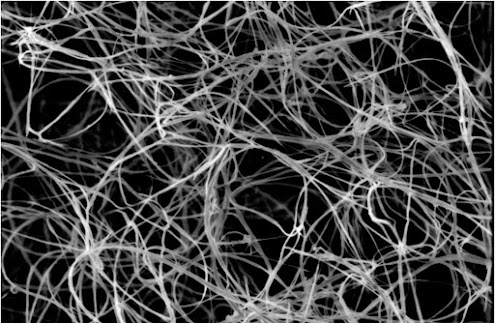

| Rendering of the process by which ancient microbes captured light with rhodopsin proteins. Credit: Sohail Wasif/UCR |

Using light-capturing proteins in living microbes, scientists have reconstructed what life was like for some of Earth’s earliest organisms. These efforts could help us recognize signs of life on other planets, whose atmospheres may more closely resemble our pre-oxygen planet.

The earliest living things, including bacteria and single-celled organisms called archaea, inhabited a primarily oceanic planet without an ozone layer to protect them from the sun’s radiation. These microbes evolved rhodopsins — proteins with the ability to turn sunlight into energy, using them to power cellular processes.

“On early Earth, energy may have been very scarce. Bacteria and archaea figured out how to use the plentiful energy from the sun without the complex biomolecules required for photosynthesis,” said UC Riverside astrobiologist Edward Schwieterman, who is co-author of a study describing the research.

Rhodopsins are related to rods and cones in human eyes that enable us to distinguish between light and dark and see colors. They are also widely distributed among modern organisms and environments like saltern ponds, which present a rainbow of vibrant colors.

.jpg)