|

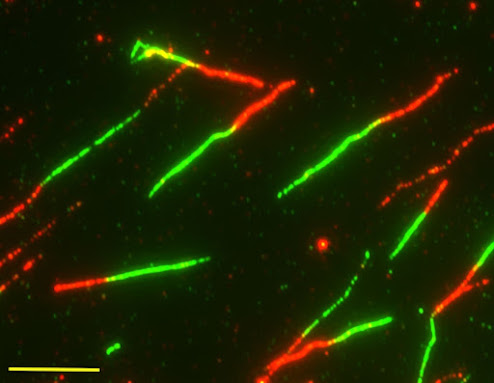

| Circulating antibody (white) is prevented from accessing olfactory epithelium (green) by a previously unknown blood-olfactory barrier, the BOB. Credit: Ashley Moseman Lab, Duke University |

Duke scientists have identified a previously unknown barrier that separates the bloodstream from smelling cells in the upper airway of mice, likely as a way to protect the brain.

But this barrier also ends up keeping some of the larger molecules of the body’s immune system out, and that may be hindering the effectiveness of vaccines.

It makes sense to have a protective barrier for the olfactory cells lining the nose, because they offer a direct path to the olfactory bulb of the brain, making them effectively extensions of the brain itself, said lead researcher Ashley Moseman, an assistant professor of immunology in the Duke School of Medicine.

However, the new barrier, which his team has dubbed the BOB – the blood-olfactory barrier -- also might be keeping vaccines against respiratory viruses from being more effective by preventing those antibodies from reaching the mucous on the surface of the nose, the first barrier a virus encounters.

The team was trying to understand better how the immune system protects the upper respiratory tract by infecting mice with a virus called vesicular stomatitis virus, or VSV, that is known to penetrate to the central nervous system. Once inhaled, VSV readily infects the olfactory sensing cells and rapidly replicates, reaching the olfactory bulb of the brain within a day. Although it can lead to paralysis and death, it is usually cleared by a T cell response.

.jpg)

.jpg)