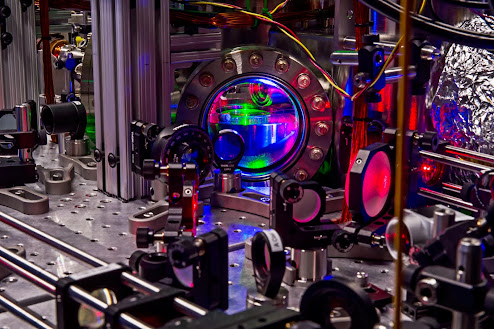

Gray and white flecks skitter erratically on a computer screen. A towering microscope looms over a landscape of electronic and optical equipment. Inside the microscope, high-energy, accelerated ions bombard a flake of platinum thinner than a hair on a mosquito’s back. Meanwhile, a team of scientists studies the seemingly chaotic display, searching for clues to explain how and why materials degrade in extreme environments.

Based at Sandia, these scientists believe the key to preventing large-scale, catastrophic failures in bridges, airplanes and power plants is to look — very closely — at damage as it first appears at the atomic and nanoscale levels.

“As humans, we see the physical space around us, and we imagine that everything is permanent,” Sandia materials scientist Brad Boyce said. “We see the table, the chair, the lamp, the lights, and we imagine it’s always going to be there, and it’s stable. But we also have this human experience that things around us can unexpectedly break. And that’s the evidence that these things aren’t really stable at all. The reality is many of the materials around us are unstable.”

.jpg)