|

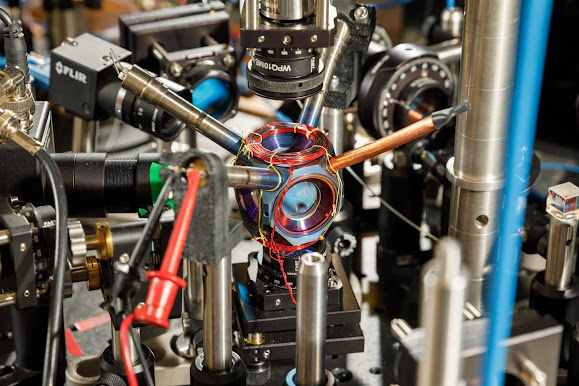

| A compact device designed and built at Sandia National Laboratories could become a pivotal component of next-generation navigation systems. (Photo by Bret Latter) |

Don’t let the titanium metal walls or the sapphire windows fool you. It’s what’s on the inside of this small, curious device that could someday kick off a new era of navigation.

For over a year, the avocado-sized vacuum chamber has contained a cloud of atoms at the right conditions for precise navigational measurements. It is the first device that is small, energy-efficient and reliable enough to potentially move quantum sensors — sensors that use quantum mechanics to outperform conventional technologies — from the lab into commercial use, said Sandia National Laboratories scientist Peter Schwindt.

Sandia developed the chamber as a core technology for future navigation systems that don’t rely on GPS satellites, he said. It was described earlier this year in the journal AVS Quantum Science.

Countless devices around the world use GPS for wayfinding. It’s possible because atomic clocks, which are known for extremely accurate timekeeping, hold the network of satellites perfectly in sync.

But GPS signals can be jammed or spoofed, potentially disabling navigation systems on commercial and military vehicles alike, Schwindt said.

So instead of relying on satellites, Schwindt said future vehicles might keep track of their own position. They could do that with on-board devices as accurate as atomic clocks, but that measure acceleration and rotation by shining lasers into small clouds of rubidium gas like the one Sandia has contained.

.jpg)