|

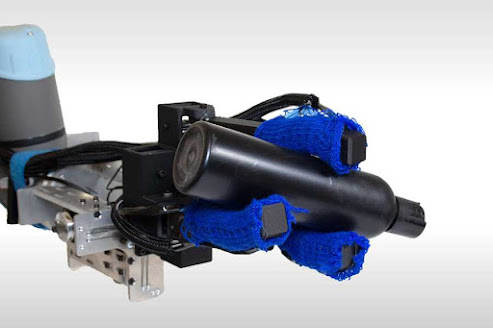

| MIT researchers have created an integrated design pipeline that enables a user with no specialized knowledge to quickly craft a customized 3D-printable robotic hand. Credits: Lara Zlokapa |

MIT researchers have created an interactive design pipeline that streamlines and simplifies the process of crafting a customized robotic hand with tactile sensors.

Typically, a robotics expert may spend months manually designing a custom manipulator, largely through trial-and-error. Each iteration could require new parts that must be designed and tested from scratch. By contrast, this new pipeline doesn’t require any manual assembly or specialized knowledge.

Akin to building with digital LEGOs, a designer uses the interface to construct a robotic manipulator from a set of modular components that are guaranteed to be manufacturable. The user can adjust the palm and fingers of the robotic hand, tailoring it to a specific task, and then easily integrate tactile sensors into the final design.

Once the design is finished, the software automatically generates 3D printing and machine knitting files for manufacturing the manipulator. Tactile sensors are incorporated through a knitted glove that fits snugly over the robotic hand. These sensors enable the manipulator to perform complex tasks, such as picking up delicate items or using tools.

.jpg)