|

| The silicide research team. In the front from left to right: Mark Hersam, Michael Bedzyk, James Ronidnelli and Xiezeng Lu. Back: Carlos Torres and Dominic Goronzy. Photo Credit: SQMS Center |

Just as the sound of a guitar depends on its strings and the materials used for its body, the performance of a quantum computer depends on the composition of its building blocks. Arguably the most critical components are the devices that encode information in quantum computers.

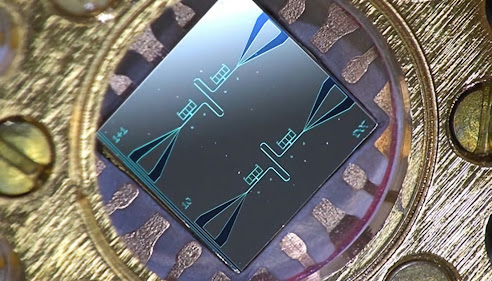

One such device is the transmon qubit — a patterned chip made of metallic niobium layers on top of a substrate, such as silicon. Between the two materials resides an ultrathin layer that contains both niobium and silicon. The compounds of this layer are known as silicides (NbxSiy). Their impact on the performance of transmon qubits has not been well understood — until now.

Silicides form when elemental niobium is deposited onto silicon during the fabrication process of a transmon qubit. They need to be well understood to make devices that reliably and efficiently store quantum information for as long as possible.

Researchers at the Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center, hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, have discovered how silicides impact the performance of transmon qubits. Their research has been published in APS Physical Review Materials.

.jpg)

.jpg)

_1.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)