|

| The radiation residue from the Big Bang, distorted by dark matter 12 billion years ago. Credit: Reiko Matsushita |

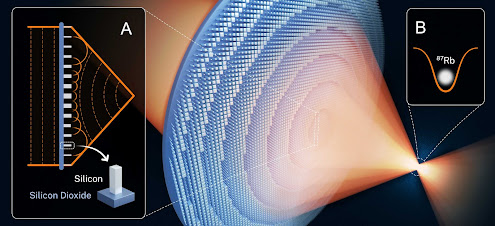

A collaboration led by scientists at Nagoya University in Japan has investigated the nature of dark matter surrounding galaxies seen as they were 12 billion years ago, billions of years further back in time than ever before. Their findings, published in Physical Review Letters, offer the tantalizing possibility that the fundamental rules of cosmology may differ when examining the early history of our universe.

Seeing something that happened such a long time ago is difficult. Because of the finite speed of light, we see distant galaxies not as they are today, but as they were billions of years ago. But even more challenging is observing dark matter, which does not emit light.

Consider a distant source galaxy, even further away than the galaxy whose dark matter one wants to investigate. The gravitational pull of the foreground galaxy, including its dark matter, distorts the surrounding space and time, as predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity. As the light from the source galaxy travels through this distortion, it bends, changing the apparent shape of the galaxy. The greater the amount of dark matter, the greater the distortion. Thus, scientists can measure the amount of dark matter around the foreground galaxy (the “lens” galaxy) from the distortion.

However, beyond a certain point scientists encounter a problem. The galaxies in the deepest reaches of the universe are incredibly faint. As a result, the further away from Earth we look, the less effective this technique becomes. The lensing distortion is subtle and difficult to detect in most cases, so many background galaxies are necessary to detect the signal.

.jpg)