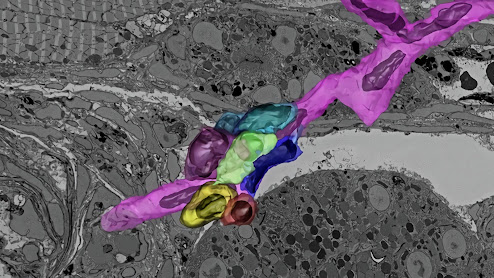

A new study corrects an important error in the 3D mathematical space developed by the Nobel Prize–winning physicist Erwin Schrödinger and others and used by scientists and industry for more than 100 years to describe how your eye distinguishes one color from another. The research has the potential to boost scientific data visualizations, improve TVs and recalibrate the textile and paint industries.

“The assumed shape of color space requires a paradigm shift,” said Roxana Bujack, a computer scientist with a background in mathematics who creates scientific visualizations at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Bujack is lead author of the paper by a Los Alamos team in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science on the mathematics of color perception. "Our research shows that the current mathematical model of how the eye perceives color differences is incorrect. That model was suggested by Bernhard Riemann and developed by Hermann von Helmholtz and Erwin Schrödinger — all giants in mathematics and physics — and proving one of them wrong is pretty much the dream of a scientist.”

Modeling human color perception enables automation of image processing, computer graphics and visualization tasks.

.jpg)