|

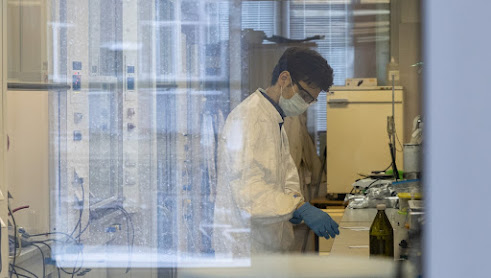

| Boron-based glass is one of the best known and highest quality systems. Photo credit: Ilya Safarov |

Physicists at Ural Federal University, together with colleagues from universities in Germany, Pakistan, and Egypt, have synthesized new glass with outstanding radiation protection properties. The glass can be used in such fields as nuclear medicine, astronaut spacesuits, and spacecraft production. An article about the research was published in the Journal of Inorganic and Organometallic Polymers and Materials.

A novel boro-bariofluoride sodium calcium nickel glasses were created using a conventional melt-hardening technique. By heating the composition to melting temperature and then abruptly cooling it to room temperature, the researchers obtained a homogeneous mixture of boron oxide, barium fluoride, calcium oxide, sodium oxide, and nickel oxide.

"Research of physical and optical properties of glasses synthesized in this way showed that as nickel oxide is added to the composition, all optical characteristics of the initial boro-bariofluoride and sodium-calcium glass samples obtained from it improve. The density of glasses increases, the absorption spectrum increases, shifting towards longer wavelengths of radiation, and the ability of the system to shield photons carrying electromagnetic radiation increases," explains Ali Abouhaswa, Senior Researcher of the Section of Solid State Magnetism at UrFU, a co-author of the article.

According to the scientist, the adding of nickel oxide makes the glass applicable to optoelectronic and photoelectric devices, such as gas sensors, UV-photosensors, photovoltaic cells, photocatalysts, and electrochromic devices.

.jpg)