Solar panels, also known as photovoltaics, rely on semiconductor devices, or solar cells, to convert energy from the sun into electricity.

To generate electricity, solar cells need an electric field to separate positive charges from negative charges. To get this field, manufacturers typically dope the solar cell with chemicals so that one layer of the device bears a positive charge and another layer a negative charge. This multilayered design ensures that electrons flow from the negative side of a device to the positive side – a key factor in device stability and performance. But chemical doping and layered synthesis also add extra costly steps in solar cell manufacturing.

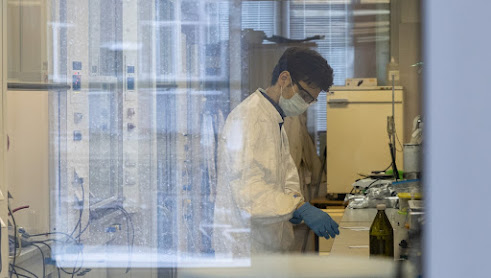

Now, a research team led by scientists at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), in collaboration with UC Berkeley, has demonstrated a unique workaround that offers a simpler approach to solar cell manufacturing: A crystalline solar material with a built-in electric field – a property enabled by what scientists call “ferroelectricity.” The material was reported earlier this year in the journal Science Advances.

.jpg)