|

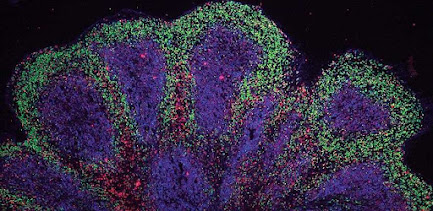

| Organoids: The Science and Ethics of Mini-Organs Image Credit: Scientific Frontline / AI generated |

The "At a Glance" Summary

- Defining the Architecture: Unlike traditional cell cultures, organoids are 3D structures grown from pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or adult stem cells. They rely on the cells' intrinsic ability to self-organize, creating complex structures that mimic the lineage and spatial arrangement of an in vivo organ.

- The "Avatar" in the Lab: Organoids allow for Personalized Medicine. By growing an organoid from a specific patient's cells, researchers can test drug responses on a "digital twin" of that patient’s tumor or tissue, eliminating the guesswork of trial-and-error prescriptions.

- Bridge to Clinical Trials: Organoids serve as a critical bridge between the Petri dish and human clinical trials, potentially reducing the failure rate of new drugs and decreasing the reliance on animal testing models which often fail to predict human reactions.

- The Ethical Frontier: As cerebral organoids (mini-brains) become more complex, exhibiting brain waves similar to preterm infants, science faces a profound question: At what point does biological complexity become sentience?

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)