|

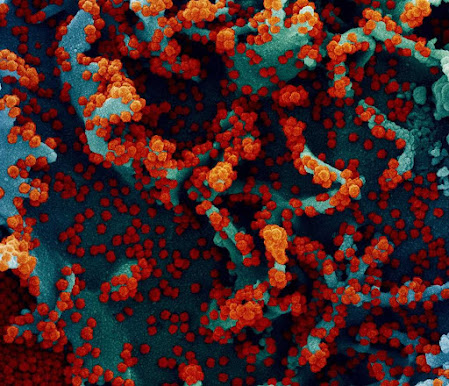

China's famous Red Marshes, a protected area and vital shorebird

habitat that is increasingly being overrun by invasive grasses

that are smothering the red plants.

Photo credit: Hong'an Ding |

The iconic “Red Beach” marshes of China’s Yellow Sea are a critical stopover for millions of shorebirds on their seasonal migrations along the East Asian-Australasian Flyway.

But in recent years, the vivid scarlet-hued native succulent plants that give the marshes their name are increasingly being overrun by non-native invasive grasses that are turning the marshes, which the Chinese government has set aside as a protected area, into a green desert avoided by shorebirds.

A new international study suggests similar scenarios may be playing out in many protected areas worldwide.

“Invasive species such as the cordgrass that is swamping native plants in the Red Marshes pose a much greater threat to protected areas, even well managed ones, than was previously recognized,” says Brian Silliman, Rachel Carson Distinguished Professor of Marine Conservation Biology at Duke University, who co-authored the study.

“Our findings suggest it may no longer be enough to defend these coastal areas of great ecological importance from disturbances by human activities,” says lead author Qiang He, a former postdoctoral researcher in Silliman’s lab who is now a professor of coastal ecology at Fudan University in China. “We also need to find better ways to protect them from biological invaders like cordgrass, which thrive in the open habitat of low-elevation mudflats that are a preferred habitat of shorebirds and common at many of these sites.”

Silliman, He and their colleagues published their peer-reviewed study Oct. 13 in the journal Science Advances. It was selected by the journal’s editors to be the issue’s cover article.

To conduct their study, the researchers used remote sensing to analyze 30 years of Google Earth Engine satellite images of wetlands inside and outside of seven of China’s largest protected coastal areas on the Yellow Sea, including several World Natural Heritage sites and Wetlands of International Importance sites.

By measuring and comparing the speed and extent of both wetland loss - typically caused by human disturbance – and cordgrass invasion at each site, they were able to construct a time-series dataset that shows native plants and habitats within the protected areas do receive protection, just not always enough.

“Although wetland loss due to human disturbance was significantly slower in all protected areas than in the unprotected control sites, plant invasions were much higher in four of the protected areas under invasion,” says He.

That finding confounds the prevailing theory that disturbance promotes species invasions, says Silliman.

“Compared to protected areas, unprotected sites often experience strong human disturbance, have more open habitats and are, thus, expected to be more vulnerable to invasions by exotic species,” he says. “We found it’s not that cut and dried.”

“Most importantly, our findings caution blind acceptance of the current conservation paradigm that protected areas will work well as long as human activities are managed effectively. This study shows that even if they are, invasive species can wreck that feel-good party,” he says. Silliman directs the Duke Restore initiative, which brings together researchers from science, engineering and policy to develop more effective tools and practices to combat habitat loss and enhance the resilience of natural and human systems in coastal areas. Qiang He is a visiting scholar in the program.

Their new study’s publication coincided with the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP15) United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in Kunming, China.

Leaders from more than 100 nations attended the meeting. They called for “urgent and integrated action” to increase the emphasis placed on biodiversity protection in all sectors of the global economy but stopped short of committing to specific targets to slow species loss, including a long-debated proposal to protect or conserve 30% of the land and ocean within their national territories by 2030.

Funding for the new study came from the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the National Key Research and Development Program of China.

Source/Credit: Duke University/Brian Silliman

en101721_01

.jpg)