|

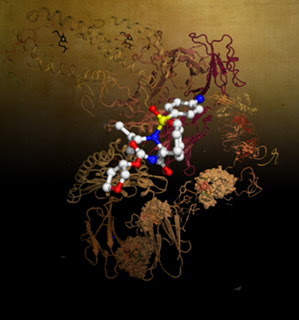

| Research illuminating an elusive component of the adaptive immune system, how gamma delta T cells sense the metabolite-antigen presenting molecule MR1. Artwork image created by Dr Erica Tandori. |

T cells communicate with other cells in the body in search of infections or diseases. This crosstalk relies on specialized receptors known as T cell receptors that recognize foreign molecular fragments from an infection or cancer that are presented for detection by particular molecules called major histocompatibility complex (MHC) or MHC-like.

In this study, Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute scientists have expanded the understanding of how a poorly defined class of gamma delta T cells recognizes an MHC-like molecule known as MR1. MR1 is a protein sensor that takes cellular products generated during infections or disease and presents them for T cells to detect, thereby alerting the immune system.

These gamma delta T cells play an understudied role within specific tissues around the body including the intestinal tract and may be an important factor in diseases that impact these tissues.

The findings are published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study was co-led by Dr Benjamin S. Gully and Dr Martin Davey with first author Mr Michael Rice from the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute.

Mr Rice, a PhD student in the Rossjohn lab, says the more we understand how such cells recognize, interact with and even kill infected, diseased or cancerous cells, the greater informed we are when developing therapies and treatments for a range of conditions.

“Gamma delta T cells are key players in the immune response to infected and cancerous cells, yet we know very little about how they mediate these important functions,” said Mr Rice.

By using a high-intensity X-ray beam at the Australian Synchrotron, the scientists were able to obtain a detailed 3D atomic model of how the gamma delta T cell receptor recognizes MR1. What sets these cells apart from others seems to be the unusual ways in which they interact with MR1. This work further recasts our understanding of how T cell receptors can interact with specialized MHC-like molecules and represents a notable development for our understanding of T cell biology.

Mr Rice stated: “By using high-resolution protein imaging and biochemical assays, we were able to identify key mechanisms that govern gamma delta T cell receptor recognition of MR1, a key sensor of bacterial infection.”

Co-lead author Dr Gully said: “These cells have evaded characterization for a long time, leading to many assumptions on how they become activated. Here we have shown that these gamma delta T cells can recognize MHC-like molecules in their own unique ways and in ways we could not have predicted.

“These results will now inform our attempts to understand the roles of these gamma delta T cells within the tissues in which they are found, and in deciphering their roles within disease.”

Dr Davey said: “These are important T cells that form a major component of the immune system within human tissues such as the lungs and gastrointestinal tract. With a greater understanding of how our immune system operates within these tissues, we can reveal crucial insight into disease.

“A better understanding of these tissue-specific T cells could reveal their power as a new line of immunotherapies for infection and cancer immunotherapy.”

The study represented a cross-disciplinary collaboration between researchers from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Monash Centre for Innate Immunity and Infectious Diseases and Monash University. The research findings involved collaborative support from Australian scientists, the ARC Centre of Excellence in Advanced Molecular Imaging, and the use of the Australian Synchrotron. This research was supported by funding from the Rebecca L. Cooper Medical Research Foundation, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the NIH, National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Research Council.

Source/Credit: Monash University

scn113021_01

.jpg)