|

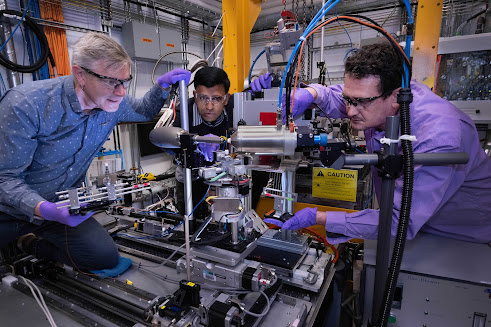

| Credit: Victor O. Leshyk/Northern Arizona University |

“As ecologists, we generally don’t think about soil metabolism in terms of pathways,” said Paul Dijkstra, research professor of biology in the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society at NAU and lead author of the study. “But we now have evidence that metabolism differs from soil to soil. We’re the first to see that.”

“We’ve learned that biochemistry—more specifically, the metabolic pathways the soil microbiota chooses—matters, and it matters a lot,” said co-author Michaela Dippold, a professor of bio-geosphere interactions at University of Tübingen in Germany. “Our field urgently needs to develop experimental approaches that quantify maintenance energy demand and underlying respiration in a robust way. It’s a challenge to which future soil ecology research will have to respond.”

.jpg)