|

| Prof. Andrej Pustogow Photo Credit: Courtesy of TU Wien |

The simplest explanation is often the best - this also applies to fundamental science. Researchers from TU Wien and Toho University recently showed that a supposed quantum spin liquid can be described by more conventional physics.

For two decades, it was believed that a possible quantum spin liquid was discovered in a synthetically produced material. In this case, it would not follow the laws of classical physics even on a macroscopic level, but rather those of the quantum world. There is great hope in these materials: they would be suitable for applications in quantum entangled information transmission (quantum cryptography) or even quantum computation.

Now, however, researchers from TU Wien and Toho University in Japan have shown that the promising material, κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3, is not the predicted quantum spin liquid, but a material that can be described using known concepts.

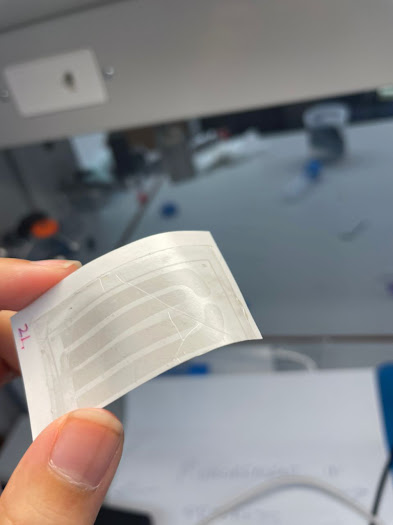

In their recent publication in the journal "Nature Communications", the researchers report how they investigated the mysterious quantum state by measuring the electrical resistance in κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3 as a function of temperature and pressure. In 2021, Andrej Pustogow from the Institute of Solid-State Physics at TU Wien has already investigated the magnetic properties of this material, opens an external URL in a new window.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)