|

| Images courtesy of Matt Bertone and Adrian Smith. |

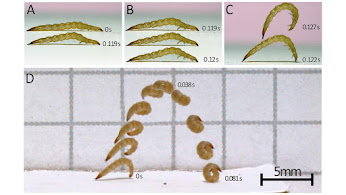

The previously unrecorded behavior occurs in the larvae of a species of lined flat bark beetle (Laemophloeus biguttatus). Specifically, the larvae are able to spring into the air, with each larva curling itself into a loop as it leaps forward. What makes these leaps unique is how the larvae are able to pull it off.

“Jumping at all is exceedingly rare in the larvae of beetle species, and the mechanism they use to execute their leaps is – as far as we can tell – previously unrecorded in any insect larvae,” says Matt Bertone, corresponding author of a paper on the discovery and director of North Carolina State University’s Plant Disease and Insect Clinic.

While there are other insect species that are capable of making prodigious leaps, they rely on something called a “latch-mediated spring actuation mechanism.” This means that they essentially have two parts of their body latch onto each other while the insect exerts force, building up a significant amount of energy. The insect then unlatches the two parts, releasing all of that energy at once, allowing it to spring off the ground.

.jpg)