Even many successful people harbor what is commonly called impostor syndrome, a sense of being secretly unworthy and not as capable as others think. First posited by psychologists in 1978, it is often assumed to be a debilitating problem.

But research by an MIT scholar suggests this is not universally true. In workplace settings, at least, those harboring impostor-type concerns tend to compensate for their perceived shortcomings by being good team players with strong social skills, and are often recognized as productive workers by their employers.

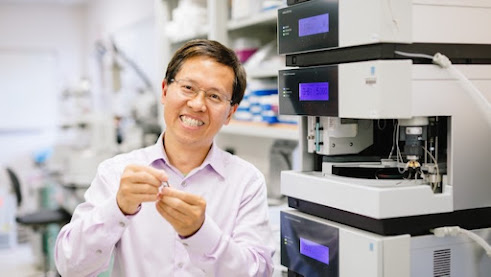

“People who have workplace impostor thoughts become more other-oriented as a result of having these thoughts,” says Basima Tewfik, an assistant professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management and author of a new paper detailing her findings. “As they become more other-oriented, they’re going to be evaluated as being more interpersonally effective.”

Tewfik’s research as a whole suggests we should rethink some of our assumptions about impostor-type complexes and their dynamics. At the same time, she emphasizes, the prevalence of these types of thoughts among workers should not be ignored, dismissed, or even encouraged.

.jpg)