|

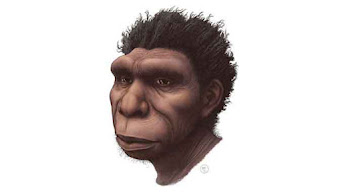

| Artist's impression of dinosaur extinction Credit: James McKay |

The gases were ejected into the Earth’s atmosphere after a six-mile-wide asteroid hit what is now the Yucatan Peninsula, around 66 million years ago.

The research, published today in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) in collaboration with Syracuse University (New York, US), and Texas A&M explored the consequences of the asteroid impact known as the Chicxulub impact.

The research team found that Sulphur gases circulated globally for years in the Earth’s atmosphere, cooling the climate and contributing to the mass extinction of life. This extinction event was catastrophic for dinosaurs and other life but also allowed for the diversification of mammals including primates.

Dr James Witts of the School of Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol said: “Our data provides the first direct evidence for the massive amounts of Sulphur released by the Chicxulub impact. It’s amazing to be able to see such rapid and catastrophic global change in the geological record.”

Dr Aubrey Zerkle of the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of St Andrews, explained: “One reason this particular impact was so devastating to life seems to be that it landed in a marine environment that was rich in Sulphur and other volatiles. The dinosaurs were just really unlucky!”

.jpg)