|

| Scott D. Pegan, a professor of biomedical sciences Photo Source: University of California, Riverside |

A research team led by the University of California, Riverside, has discovered important details about how therapeutically relevant human monoclonal antibodies can protect against Crimean Congo Hemorrhagic Fever virus, or CCHFV. Their work, which appears online in the journal Nature Communications, could lead to the development of targeted therapeutics for infected patients.

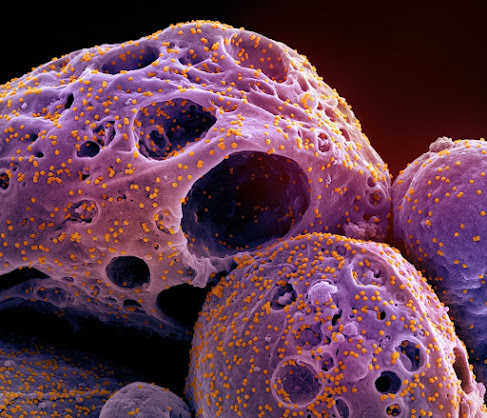

An emerging zoonotic disease with a propensity to spread, CCHF is considered a priority pathogen by the World Health Organization, or WHO. CCHF outbreaks have a mortality rate of up to 40%. Originally described in Crimea in 1944–1945, and decades later in the Congo, the virus has recently spread to Western Europe through ticks carried by migratory birds. The disease is already endemic in Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East, and some Asian countries. CCHFV is designated as a biosafety level 4 pathogen (the highest level of biocontainment) and is a Category A bioterrorism/biological warfare agent. There is no vaccine to help prevent infection and therapeutics are lacking.

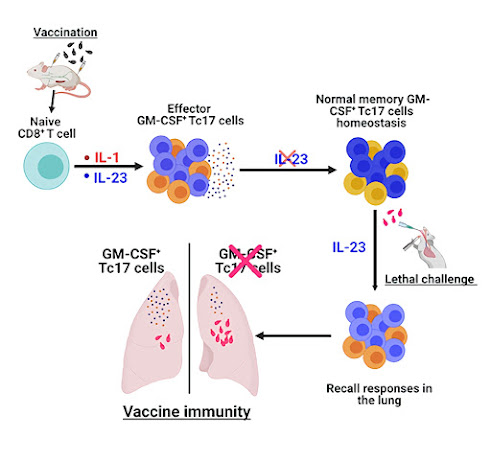

Scott D. Pegan, a professor of biomedical sciences in the UCR School of Medicine, collaborated on this study with the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, or USAMRIID, which studies CCHFV because of the threat it poses to military personnel around the world. They examined monoclonal antibodies, or mAbs, which are proteins that bind to antigens — foreign substances that enter the body and cause the immune system to mount a protective response.

In a previous publication, USAMRIID scientists Joseph W. Golden and Aura R. Garrison reported that an antibody called 13G8 protected mice from lethal CCHFV when administered post-infection. They provided Pegan with the sequence information for that antibody, clearing the way for UCR to “humanize” it and conduct further research.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)