.jpg) |

| Dr. Tanveer Sharif Photo Credit: Courtesy of University of Manitoba |

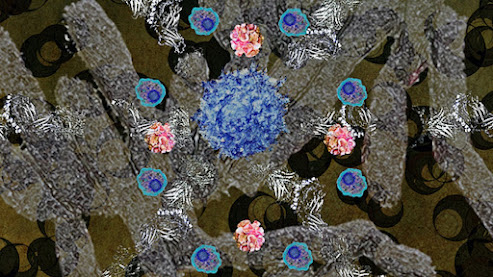

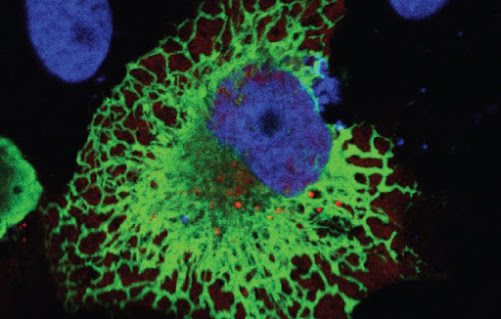

A discovery made by a University of Manitoba researcher could lead to safer and more effective treatments for childhood brain cancer.

Dr. Tanveer Sharif, assistant professor of pathology at the Max Rady College of Medicine, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, is studying a childhood brain cancer called Group 3 medulloblastoma and he’s developed an approach to target cancer cells using precision medicine.

“Brain tumors are the leading cause of cancer-related death in people under the age of 20 and medulloblastoma is the most common childhood brain malignancy,” said Sharif, who is a Canadian Cancer Society Emerging Scholar. “Current treatment options for this deadly cancer are very toxic and haven’t changed much over the last 20 years. For patients who do survive, they suffer from long-lasting side effects linked to chemotherapy and radiation treatments. There is an urgent need to have a safer therapeutic strategy for medulloblastoma.”

Sharif’s findings were published today in Nature Communications, and his research is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)