|

| The structure of the protein behind NF1 has been discovered. |

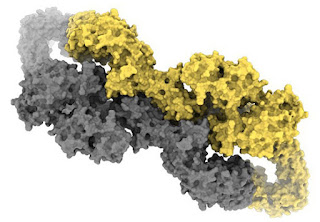

A collaboration between Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute (BDI) and the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MIPS) used cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to take high-resolution pictures revealing the complex shape of the protein. The detailed pictures will help scientists better understand how the protein works, how it is changed by genetic mutation and could lead to new strategies for treatment.

The study was co-led by BDI’s Dr Andrew Ellisdon and Associate Professor Michelle Halls from MIPS and is now published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

NF1 or Von Recklinghausen's disease is an extremely variable condition affecting one in 2500 Australians. Most people with it will never be impacted by major medical complications; for others, the condition can be debilitating and life-threatening. There is no known cure and treatment options are limited. People with NF1 have a higher risk of developing a number of cancers, and the protein itself is mutated in cancers in people who don’t have the condition.

Dr Ellisdon stated: “When we lose function in that protein it basically takes away a ‘stop’ signal for cell growth and we get the formations of tumors in the body.”

The gene for NF1 was discovered in 1990 by a group of US scientists but until now researchers had no idea what the protein looked like.

“Most of the techniques we’ve had up until recently haven’t been able to take images at a high enough resolution to understand what the shape or structure the protein is,” Dr Ellisdon said.

“What we were able to do at Monash was harness recent developments in powerful cryogenic electron microscopy to take the first high-resolution images of this protein.”

Co-lead author Associate Professor Halls said: “The other interesting thing was when we solved the structure we found the protein was folded in quite an intricate way and is twisted so you could have mutations in lots of different parts of the protein, all with similar detrimental effects on the protein’s function.

“We were able to map the different genetic mutations that are associated with NF1. Hopefully, we’ll be able to associate mutations with particular outcomes in the cell.”

The scientists’ long-term aim is to inform better models of disease progression, which would be beneficial to patients, and to discover potential new treatments.

Instrumental to the study were the first authors Drs Christopher Lupton, Charles Bayly-Jones and Laura D’Andrea at Monash BDI. The study was originally funded by the BDI and then expanded into a larger program across several research groups, funded by the Medical Research Future Fund.

Source/Credit: Monash University

bio121321_01

.jpg)